Soundboard

The Steinway & Sons Podcast

Sean Jones

Sean Jones is the bandleader for NYO Jazz (Carnegie Hall’s Jazz National Youth Orchestra) and drops by Soundboard to talk jazz, race, and music education. Jones is a former first trumpeter the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and holds the Richard and Elizabeth Case Chair in Jazz Studies at the Peabody Conservatory of John Hopkins University. He was interviewed at New York City’s Carnegie Hall by Soundboard producer/host Ben Finane, our Editor in Chief and Editor in Chief at Steinway’s award-winning online music magazine listenmusicculture.com.

[Below is an edited transcript of the podcast.]

Ben Finane: Here’s why I’m talking to you today. I went to the Carnegie Hall season announcement. And I love Carnegie Hall, but the season announcement is the season announcement: I know what’s going to happen. I know it’s a Beethoven year. I bet Anne-Sophie Mutter is going to be on the program somewhere. I’m not expecting them to say, “Ladies and gentlemen, this year’s Composer’s Chair is Chuck D!” Then, in a clip Carnegie had done for NYO Jazz, you said something to the effect of: “Jazz celebrates what is best in America and it also reveals what America has tried to sweep under the rug.” And that really knocked me out — because I know that it’s true. I know it’s true and I knew it was true the more I thought about it. But to hear it really made me start thinking, because I think some of the received narrative about jazz right now is: jazz has led to hip-hop, and hip-hop is now the prime musical expression for African Americans. And the received narrative from hip-hop is: in the Bronx, these kids didn’t have money in their schools for instruments, they made the turn table into an instrument, et cetera et cetera. But if we go back farther than that, what you said is true about jazz. It’s absolutely true. I wonder if we could just start with you unpacking your statement.

Sean Jones: Well, there are so many layers there to this that it’s impossible to unpack it all in a short period of time, but the one thing that I will say is that in the American condition, not just black people, but Americans in general have all had to find ways to survive and create through survival, right? What I mean by survival is, if we just look at the economic lenses that we deal with: people not having as much or just having enough to be able to survive, right? Well, survival isn’t just about eating food. It isn’t just about having water. It’s about being able to express yourself as a human being. That’s a part of our survival. And so when you don’t have economic means to have an instrument, to have access to arts programs, teachers, et cetera, you take anything and you make it work. Well, what would the black people do at the turn of the century (1900s)? They took old war instruments, and the music that they heard, which was predominantly art music, predominantly marching-band music, and they flipped it — added different elements of time to it, started bending notes.

That was technology, right? We look at technology in a weird way, like it’s something that you plug into somewhere. No. Technology is an invention or a way to take something that exists and manipulate it so that something else forms out of it, okay? That’s technological advance. And so they took these coronets, these clarinets, these things, and they started to transform what was there into something new. Yes, hip-hop comes out of jazz and hip-hop does that right now. Yes. But it’s just an extension of what has been the African American condition in this country from its inception.

‘The artist’s purpose is to unlock the chains that the world has put itself in: economics, division, Hammurabi’s Code.’

So this is a changing of musical language and it reminds me what James Baldwin said, that English language changed for black folks because the language as it was could not possibly encapsulate the black experience.

That’s correct. That is correct.

Do you see a parallel there?

There is a parallel, a direct parallel, in that if you take a march, a Sousa, you know, any of them, any march [sings Stars and Stripes Forever straight as written.] You just gestured the square, right?

Yeah, foursquare.

Foursquare. It’s not really square, it’s just a thing: it’s what it is, okay? Now what African Americans did was we took what is innately inside of us, rhythmic components, playing off the beat, all of that bending and swooping, all of the things that we brought over here — and we added that naturally [sings Stars and Stripes Forever, swung.] That’s African, you know what I mean? But at the same time, it’s human. The thing that I worry about in this country is that we divorce ourselves from one another, you know? Like I’m looking at you across the table, right, you’re clearly a white guy, and I’m clearly a black guy, but we just have experiences that have informed who we are based on where we come from, where they came from that raised us, x, y, and z. But it all comes back to the same stuff, man. You know?

That’s important, too. If you were me, you’d be the same way.

Exactly.

That’s empathy. That’s empathy that jazz is bringing and that hopefully the arts are bringing.

Right, and that’s our purpose. Our purpose is to unlock the chains that the world has put themselves in: economics, division, Hammurabi’s Code, all of these things that have, from those sources, attempted to divide us. It’s the artist’s job to unlock the change and say, “We are the same.” That’s what jazz has been able to do in this country, turned to hip-hop, turn to rock ‘n’ roll, turned to this, that, and the other, and at some point it would be great if America said: "We are Americans. We are this. We are informed by a multiplicity of nations, but we come from those places and became this one thing.” And I suppose that, within the next few decades, hopefully we start to progress a little bit more in that direction.

There are a lot of people who look like me in Europe, but when they walk, there’s no bounce in their step one.

There’s a bounce.

But when white Americans like myself walk, there’s more of a bounce.

Oh that’s very true.

I would like to thank that that is informed by my proximity to jazz and to other influences from African American culture.

That’s true.

I think there’s a line there between the bounce as I walk down the street and the bounce that’s in that music that you were just singing, the African Americanification of Sousa earlier.

The flip side of that is I would like to think that extended forms in harmony, extended compositional techniques, and things like that, being able to theorize those things and code them a certain way, comes from the European experience.

Absolutely.

And I’m able to do that now because Europeans exist.

Yes.

And so one being better than the other or one being superior than the other, whether it’s black, white or white, black or Asian, whatever it is — none is superior. The thing is that we cannot truly exist and rise as a human species without one another.

What did you learn working on under Wynton Marsalis for those years?

The true definition of hard work. I’ve never seen a human being work that hard in my life, literally twenty-four hours a day at times. I saw him write a Mass. Well, it was either the the Abyssinian Mass, or it was his Swing Symphony. I can’t remember which one it was, but I’m pretty sure that it was the <ass. He wrote that is six weeks, man. Six weeks: just up all night, just going thing to thing, meeting to meeting, this, that, and the other. And he became the CEO of Jazz at Lincoln Center is simply by reading about being a CEO. No one trained him. I was there. I saw it. His true genius, in my opinion, is his tenacity, his work ethic, and his vision. He’s a wonderful artist, amazing artist, wonderful human being —

But so are a lot of people, right?

But so are a lot of people. But his genius is in his work ethic and his ability to create a wonderful platform for the art form Jazz. Some people disagree with how he feels about it, he disagrees with some things that you say. Some things that that he says I don’t necessarily agree with, but we’re all different.

And he’s entitled to his aesthetic view of jazz.

He totally is and I appreciate my time with that band. I appreciate my time with him. He’s like a big brother to me, and I’ll just say that his true genius, in my opinion, is his work ethic.

Now you’re in a mentor role as bandleader of NYO Jazz, which is the Jazz National Youth Orchestra, a program put together by Carnegie Hall.

Yeah.

These are 16-, 17-, 18-year-old budding jazz players and they come to you for some intense workshopping and shedding and touring. What do you try to pass on to them?

First thing I’ll say is it’s daunting. The older I get, the longer I’m in education, the more I realize that you can make or break a spirit with a sentence. One sentence.

You’re saying that they’re in a fragile place?

Yes. They’re in a very fragile place. They’re being fed information on a daily basis from their families, from teachers, from mentors, from people they care about, from social media.

More information than when we were kids.

Way more.

It’s crazy.

And it’s conflicting, you know? But the one thing that I try to do is just open their mind up for possibility. Anything is possible. Dream it, you can do it: just put it in the work. And so I realize at this age — I just turned 40 years old — it’s not as old as some, but it definitely is not as young as some….

I’m 42, so I’m with you.

We’re in proximity. So, I just realized now that, man, I’ve been given keys. I have keys. And when those students come through that door, and they’re ready for rehearsal, and they’re looking at me with their eyes big, not knowing what to expect, the first thing I do is get out those keys and I walk over to them, man, and I unlock the gates, unlock the chains. I free them.

Okay, that’s a beautiful metaphor, but how do you do that?

You do that by one, letting them know it’s okay to make mistakes. In fact, please do. But go after it, no matter what that is. Go after the lines on the music. Go after the phrasing. Chip a note. Miss a bar. Do all that, but do it with intention, and we’ll correct the mistakes as we go along. Two, don’t be afraid to come to me with your ideas. You are all geniuses. All of you. And I don’t know everything. The greatest leaders know that they are typically not the smartest person in the room and it’s their job to take all intellectual capacity in that environment and put it together and create a vision for it so that we can all go somewhere. Three, managing the dynamics in the room, personalities, things like that. That’s important to do. But, like I said, the biggest thing that I want to give them is freedom to be: freedom to express, freedom to unlock their chains. Again, I do that simply by just accepting them as equals. I’m not in a superior position. Being a leader doesn’t mean that you’re superior. It just means that you’re the first person out the gate to yield the sword. That’s my job. We’re all the same, I just have to be in the music that’s coming before you have to be there. So that when you get there, I can show you what’s up.

You just gotta be a day ahead.

Yeah. That’s all. That’s leadership. Leadership is not a superior position. It’s a forward position.

What has surprised me in my own limited roles in mentorship — whether it’s with my daughter or with aspiring journalists — is what I ended up learning from them.

From them, yeah. It’s funny, isn’t it?

What have been some surprising takeaways for you or encounters that you’ve had when you’re teaching and you end up learning?

The most surprising moments are when I think I know something and a student lets me know that I have no idea what I’m talking about. It’s like, “Yeah, well you know, you have this chord here and you approach it this way….” And then they say, “No man, check this out.” And it’s like, “What?” And I have a decision to make at that moment, because what I know has worked for me. It’s like, "What are you talking about? I’ve been making this cake this way for twenty-five years."

Yeah. “Get off my lawn.”

Yeah. “Get off my lawn! What are you talking about? You’re going to tell me that this new ingredient will make this cake better? Please!” So at that moment, it’s my job to yield and allow them to express themselves, because ultimately, they’re teaching themselves when they teach me. They’re reinforcing their own concept, so the more that they reinforce their concept, the better teachers they become, so I’m actually teaching them to be a better teacher.

And that’s good confidence for a student when you can pull that off, right?

Totally. But that’s the hardest thing, man. It’s like, when you think you know something, and then there’s all of a sudden a new way to learn it! It’s like, how many ways can you say the chord A-Major-7-sharp-11? How many ways can you say that the core progression ii–V-I? And they show you a new way to do it and it’s like, “What?” But that’s evolution.

When you’re traveling, and you’re carrying jazz with you —

That’s funny.

— have you had some surprising reactions when you’re overseas to your music that, again, gave you some insight?

Initially, I had many surprising reactions regarding my music. Honestly, some of the most surprising reactions are joyful reactions, like, “Wow, I really love that. Thank you, thank you, thank you for those moments.” Surprising to me, because they’re tunes. Yeah, it makes you feel good, but that exuberant? Really? That’s surprising. Other surprising reactions are, like, when someone will come up to me and say, they’ll undoubtedly say, like, “Why did you play this song this way?”

Defend your choice.

Yeah. “Defend your decision for playing this sacred piece of music in a new way like this. Defend it.” And my defense is, “I’m giving it new life.” “What do you mean new life? It’s already alive.” You know? “‘Straight, No Chaser’ is ‘Straight, No Chaser.’ Why would you destroy this like this?” It’s like, “Well, you know, ‘Straight, No Chaser’ decided to permeate in my mind and present another scenario — and so I decided to give birth to that idea that ‘Straight, No Chaser’ gave me."

And “Straight, No Chaser” can sustain many different interpretations.

Yeah, there’s just twelve notes, man. Twelve notes. It’s like Quincy Jones says: Twelve notes. Those twelve notes, once they come out of your body and go on a page or go on a recording or something like that, they live inside of that space. But, like any tree that’s planted, it starts off as a seed that then becomes a tree, which yields more seeds — that become other trees. It’s ridiculous to think that all trees are supposed to be the same. No. They’re of that tree, same grouping, yeah, but it’s not going to look the same, because it’s a new tree.

Let’s talk about this exuberance and where that might come from. And this gets back to the beginning of our conversation, talking about what America celebrates on what they hide under the rug. Can we even quantify what it is about jazz in particular that touches so many people across the world in such a way?

It’s real. It’s real and it’s birthed out of real emotion. Not saying that other musics aren’t, but specifically art musics come a lot of times from head spaces, you know? Jazz typically isn’t that. It’s almost like an unapologetic pursuit of expression of things that we find absurd in our whole lives. It’s like, “How dare I think this?” There’s an album that Duke Ellington did, it’s a double-sided album, right? It’s sort of his take on masculine and feminine anatomy, and one side of it is “Warm Valley” and the other side of it is “The Flaming Sword.” [Laughs.] I mean, that’s, you know, absurd. It’s very elegant the way that he does it, and when you listen to the one side and you listen to the other side, it is a true sonic depiction of those things, you know? And he unapologetically does that because that’s who we are: we’re human. And jazz has always done that, and it’s been a relentless quest for the music to do that. But that’s what American music does in general, man: it’s kind of like this raucous way of expressing the human condition through manipulation of sound in its extremes. We do it very well. We do it in small form, small songs, you know, little tunes that we riff off of, the American popular songs. Those songs are short, man.

The three-minute single.

Yeah, they’re short.

But some jazz tracks are long.

Some jazz tracks along because of the improvisation.

Okay. But at its core, like you said, twelve notes. “Straight, No Chaser”

At it’s core it’s simple, simple stuff…. The one thing that I’ve learned about teaching is that I can’t teach. I suck. Every year, and I’ve been teaching in a collegiate setting for the past fifteen years. I was crazy, man. For some reason, I thought to myself like, “Okay, all of my peers, they’re going on a road, they’re doing their thing. I’m going to go in a classroom, man. Someone from our generation needs to be in there early.” So I decided to do it early. And I thought I could teach in the beginning, because all I did was imitate my other teachers. Like I had a great teacher, his name is Tony Leonardi, he was a killer teacher, man. Passionate, but he was also like Whiplash, he would curse you out, at the drop of a dime ,go off. And so I tried to do some of that, "No! You guys suck! Blah blah blah, blah, blah, blah blah!" Not realizing that everyone can’t handle that, you know? That’s early on. And then as years go on, I learned that, one, that’s not me. That’s not my character. Two, like I said, it’s not going to work for everyone, and so I adjusted, right? Then I saw that I was able to reach more people with other things. Then, different classrooms are different classrooms. Like a subject inside of a physical space, with a certain audience inside of it, week after week, day after day in some cases, means something different than another subject when you see the class once a week, and it’s in a different part of campus, with different lighting, different time of day, and all of that. You need to approach that with a different spirit.

So this sounds like this was sort of a Zen journey of authenticity for you.

Yes, big time.

I can’t be someone else. I know nothing.

Yes.

Let’s go and explore and teach.

Let’s explore it together. I’ve realized that true teaching, man, it’s sort of like a dual thing: it’s apprenticeship / mentorship, andgroup learning. I go into class a lot of times and just: "We know nothing. Let’s just talk. Here’s the lesson. I’m not that good at this.”

“What do you think?”

“What do you think?” And we go down the rabbit hole together, and [snaps] undoubtedly, every single time, our humanity meets. We meet in the middle and we figure it out.

That’s another jazz metaphor right there. We go down the rabbit hole together.

Yeah.

Our humanity meets; we figure it out.

That’s it.

That’s within an ensemble, that’s audience and performers.

That’s exactly right.

Okay. Well, let’s leave it there, because I don’t think we can get more profound than that.

Cool, man. This is great, great.

[Photos: Todd Rosenberg, Conrad Louis-Charles]

Keep Listening...

-

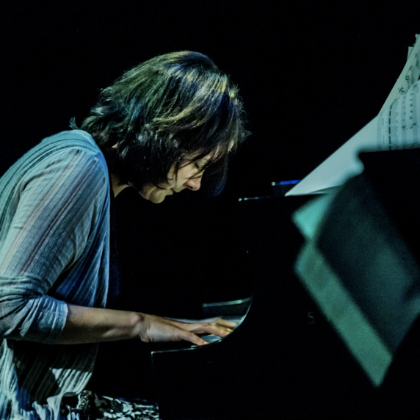

Soundboard — Kris Davis

Jazz pianist and Steinway Artist Kris Davis takes us through her process, her love of Herbie Hancock, and what she gained from listening to other instruments.

Read More -

Soundboard — Yulianna Avdeeva

Chopin International Piano Competition winner and Steinway Artist Yulianna Avdeeva discusses her most recent recording project for Pentatone: Dmitri Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87.

Read More -

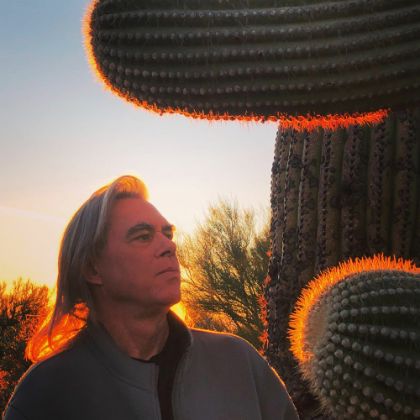

Soundboard — Steve Roach

Ambient and electronic music composer Steve Roach discusses his musical philosophy and process.

Read More -

Soundboard — Sunny War

The songwriter Sunny War talks about her eclectic influences, when less is more, her Americana dream, and taking inspiration from her racist neighbors.

Read More -

Soundboard — Nels Cline

Guitarist Nels Cline, live from Big Ears Festival, talks about having no fixed voice, Wilco, pretension, and going down with the set list.

Read More -

Soundboard — Joe Lovano

Saxophonist Joe Lovano discusses influence, tone, sound, improvisation — and what's in a name.

Read More -

Soundboard — John Paul Jones

Steinway Artist John Paul Jones, live from Big Ears Festival, talks about his influences, his sound, his process and his myriad music projects beyond Led Zeppelin.

Read More -

Soundboard — Christian McBride

Jazz bassist Christian McBride, live from Big Ears Festival, talks post-bop, remaining a bass-player-for-hire, bass-on-bass action, preparation, and jazz as democracy. Steinway & Sons is a sponsor of Jazz House Kids.

Read More -

Soundboard — Jason Moran

Jazz pianist and Steinway Artist Jason Moran, live from Big Ears Festival, talks hip hop, the next generation, the algorithm, Monk & Duke, visual art, and creative approach.

Read More -

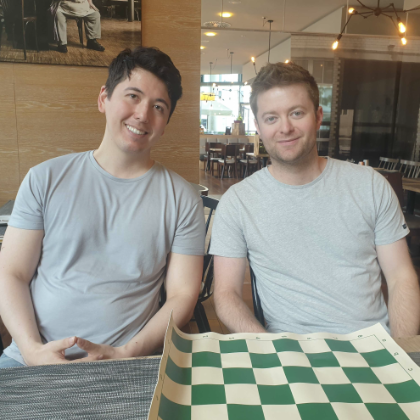

Soundboard — Chessbrah

Eric Hansen and Aman Hambleton, aka Chessbrah, talk techno and chess and what makes Magnus Carlsen the GOAT.

Read More