Listen Magazine feature

Disparate Genius

His bicentennial encourages a fuller understanding of the much-maligned Franz Liszt

By Thomas May

“FRANZ LISZT WAS a lightning rod for controversy throughout his long life, and even after: the moment he died (while attending the Bayreuth Festival in 1886), his corpse became the subject of a heated dispute. Liszt had spent his career orbiting a wide swath of Europe, so there were conflicting proposals as to where he should be interred. In spite of the claims of Hungary — the land of his birth — and the city of Weimar in central Germany — where he pursued some of his most significant musical achievements as a composer and a reformer — his daughter Cosima ended up winning the battle. She had him buried in Bayreuth near her recently deceased husband, Richard Wagner.

By keeping her father close by, literally overshadowed by Wagner’s grave, Cosima was trying to take control of Liszt’s legacy. Many have followed her lead and tend to think of Liszt as a Wagnerian pretender — a kind of entertaining sideshow to the real story of musical “progress” in the nineteenth century. Ironically, it was Liszt’s own unrelenting efforts on behalf of “the music of the future” — not only Wagner’s but other avant-garde voices of the era, including Berlioz’s — that helped establish the familiar paradigm whereby daring musical innovators are eventually vindicated by posterity.

But Liszt remains a case apart. Although recognized as a major figure of the turbulent Romantic era, his reputation remains shaky. Aficionados of his music are often forced into defensive mode, while detractors stir up a strange brew of legitimate critique and annoyingly persistent cliché. And much of the latter reverts to ad hominem attack, confusing the art with the artist.

It’s not unusual to find people who have learned to dissociate Wagner’s obnoxiousness from his music but who point disapprovingly to the Svengali–like effect Liszt was said to exert over swooning groupies (the “Liszto-mania” triggered by his virtuoso persona at the keyboard) or to the contradictions of his lifestyle: “Mephistopheles disguised as an Abbé,” in the phrase coined by a sardonic diarist. These images reinforce the caricature of Liszt as a superficial showman — or even charlatan — and make it easier to dismiss his music altogether.

‘Next to the wonderful sense of order I derived from music, I learned the value of nonsense.’

Similarly, the commonplace equation of Liszt’s superstar status as a performer to the personality cult of rock musicians skews the picture to exaggerate just one phase of his career. In fact, Liszt aroused a good deal of hostility not so much for his popularity on the concert circuit as for his promotion of convention-challenging new music.

The fact that Liszt still evokes such polarizing responses brings an unusual edge to this year’s bicentennial celebration of his birth (the actual date being October 22). Typically, a milestone anniversary serves as an excuse to either reconfirm values already agreed upon (with maybe a new discovery or two to pique interest) or revive a neglected composer. Liszt already has a secure place in the repertory, thanks to a few perennial classics, but he’s also ripe for a thoroughgoing reappraisal that digs deeper and takes account of the full range of his creative activity. There’s an exciting possibility, for once, that this year’s round of celebrations — from festival performances and new recordings to scholarly reflections — may open up new perspectives on a composer many music lovers assume they already know.

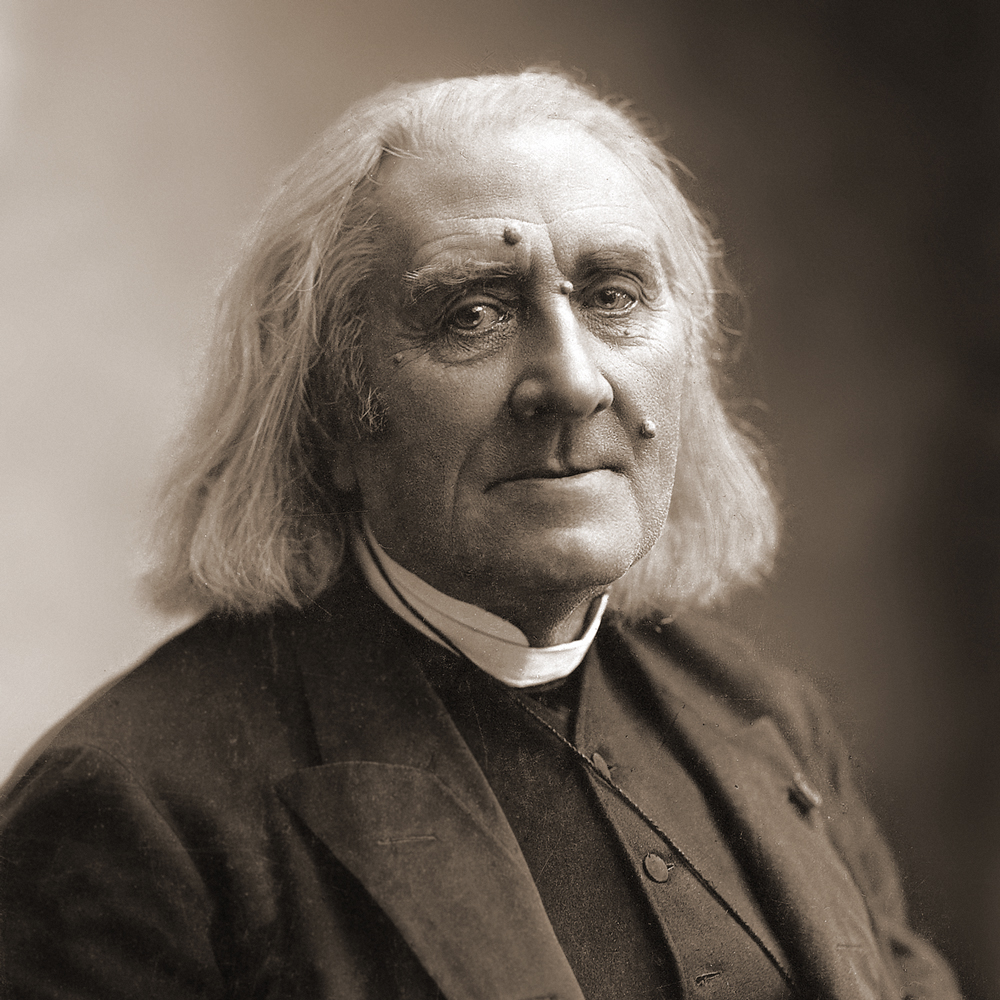

Photograph by Nadar 1866

Of course there is a familiar, almost mythic ring to Liszt’s cycles of triumph and despair. The career of this most restless of a famously restless generation epitomizes the striving we associate with romantic artists. Many of Liszt’s colleagues shared an attraction to the figure of Faust, but none of them embodied the paradoxes that entangle Goethe’s character more dramatically than Liszt did. His affairs provided some of the dishiest scandal of the era — one mistress, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, tagged him a “Don Juan parvenu.” But Liszt was no cynical libertine.

A devout Catholic, he sincerely espoused the Franciscans’ sense of compassion and love of nature. When Church politics prevented him from marrying the love of his life, the Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein (she was unable to obtain an annulment of her previous marriage), Liszt retreated inward and took minor clerical orders. His spiritual beliefs, however, involved an idiosyncratic blend of Christian socialism, mysticism and freemasonry. An intensely cosmopolitan habitué of aristocrats and royalty, Liszt voiced his support for Hungarian patriotism but remained rootless, drifting throughout his final years between Rome, Budapest and Weimar.

Liszt’s artistic career is easily divided into three periods. Alan Walker, whose magisterial and richly characterful biography offers a corrective to the lingering biases against Liszt, found it necessary to devote a separate volume to each. But these periods suggest nothing like the “early–middle–late” pattern of gradual evolution that biographers have superimposed on Beethoven’s music. In Liszt’s case, it’s almost as if three different artists are involved.

In the first period, after winning acclaim as a child prodigy, Liszt modeled himself on violinist Niccolò Paganini to perfect a style of “transcendental virtuosity” on the piano — virtuosity not as an end in itself but as the means, Liszt said, “to breathe life into the work entrusted to it.” He even invented the format of the solo recital to showcase this new musical concept of individualism, touring tirelessly from London to Istanbul. The visual dimension was an important part of the total sensual impact of his playing, and Liszt pioneered the set-up of the piano oriented sideways so his hands would be visible. “His fingers seem to stretch and grow longer,” wrote one observer, “as though they were attached to springs, and at times even seem to detach themselves from his hands altogether.”

Then, at thirty-five and at the height of his fame, Liszt gave up this extroverted career to focus on composing and conducting. He pioneered the form of the symphonic poem and focused his energy on advocating “the music of the future.”

At fifty Liszt moved on to Rome and became increasingly preoccupied with sacred music. He returned to the pattern of restless wandering, but now his musical experiments — sacred and secular — renounced romantic excess for a radical austerity, with titles like “Bagatelle Without Tonality” (a sketch for a fourth Mephisto Waltz). According to Walker, some of Liszt’s latest works, such as Nuages Gris or the Via Crucis, suggest a “gateway to modernity” (including both the Impressionists and Schoenberg), though they remain scarcely known and exerted little actual influence.

‘As an interpreter — that is, in my threefold function of curator, executor and obstetrician, I am not interested in clichés, but in what is special and unique.’

It’s remarkable that many of the complaints routinely leveled against Liszt’s music today — that it’s self-indulgent, incoherent or downright vulgar — seem little more than variations on the criticism he faced from contemporaries. While the terms of judgment which we now apply to other composers of his generation reflect profound shifts in historical awareness, those reserved for Liszt suggest the old-fashioned stubbornness of the opinionated.

After hearing Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, Eduard Hanslick, the famously staunch opponent of Wagner and Bruckner, wrote:

It is impossible to convey the nature of this musical monster in words. Never have I heard a more impudent or brazen concatenation of utterly disparate elements, such savage ravings, so bloody an assault on all that is musical. . . . Anybody who has heard this thing and liked it is beyond hope.

Nowadays the Sonata in B minor ranks among the most admired of Liszt’s major compositions (even if grudgingly so in certain quarters). Here Liszt invokes the metaphysical drama of Beethoven’s late sonatas while radically rethinking classical form, with a new, romantic focus on organic growth. But Hanslick’s sense of outrage is readily echoed by modern anti-Lisztians with regard to much of the rest of the composer’s output. The “disparate elements” Hanslick decries in the B minor Sonata — a remarkably integrated work, in fact, despite its vast emotional range — might stand as a fair description of Liszt’s career as a whole.

Its abrupt contrasts and about-faces can be perplexing, and, like his phenomenal virtuosity, have been turned against him as evidence of innate superficiality. Another source of confusion is the sheer scale and diversity of Liszt’s output. His piano music alone ranges from small character pieces to brilliantly reimagined transcriptions from opera and the orchestral literature (the entire Beethoven symphony cycle, for example). His own orchestral works include two piano concertos, symphonic poems and especially innovative scores such as the Faust Symphony, whose volatile main theme anticipates Schoenberg’s twelve-tone row. But there are also dozens of art songs, sacred choral works including two large-scale oratorios and several Masses, and significant organ pieces.

The staggering amount of music Liszt left behind has been challenging to catalog, since he was an obsessive reviser and several works exist in multiple incarnations. And even Liszt’s keenest sympathizers acknowledge the striking unevenness of his achievement. Liszt is the kind of composer who can give you a visionary thrill with one work, while another assails you with the indisputably irritating tics his detractors latch onto: the predictably repeated sequential phrases, saccharine melodies, overused diminished-seventh chords and histrionic gestures — not to mention the often dodgy orchestration.

‘While the terms of judgment we now apply to other composers of his generation reflect profound shifts in historical awareness, those reserved for Liszt suggest the old-fashioned stubbornness of the opinionated.’

But Liszt’s music also lends itself to fascinating experiences of wholesale reevaluation. The critic Andrew Porter reported a new appreciation for the massive (and rarely heard) oratorio Christus, for example, when he had the opportunity to experience it not in a concert hall but in the reverberant acoustics of New York’s St. John the Divine Cathedral. “In such a building,” Porter writes, “the repetitions in the score seem kin to the architectural repetitions, bay upon bay, that give a great cathedral its grandeur.”

To immerse yourself in Liszt — not just the familiar stuff but the wildly divergent music from across his career — is to gain a fresh perspective into the artistic obsessions of the nineteenth century. It can shed new light on this well-traveled ground, which we’ve become accustomed to viewing through the lens of such established titans as Wagner.

Take the old battle lines that are traditionally drawn between “program music” (the cause célèbre of “the music of the future”) and “absolute music.” You begin to realize what a red herring these categories are when you hear how Liszt transcends them — much as he transcends the idea of virtuosity as an end in itself — through the extraordinarily original textures of pieces like the Two Legends for keyboard. Whatever extra-musical images of St. Francis preaching to the birds are evoked, this is a self-contained world of sound, not a mere “illustration,” and it conjures a poetry all its own. The thread woven through all of Liszt’s creative disparity is the ideal he once described: “to seek the renewal of music through its inner union with poetry.”

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.