Chopin turns two hundred, with authority.

By Jed Distler

Some composers develop their style over time, while others hit their stride early on. Those who evolved step by step include Haydn, Wagner, Janáček, Scarlatti, Liszt, Glass and Carter. Other composers appeared seemingly fully formed, including Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Richard Strauss, Saint-Saëns and Boulez. As both pianist and composer, Frédéric Chopin’s genius manifested itself from the start. At eight, the budding prodigy had his first composition published (a polonaise) and made his debut as a piano soloist with orchestra. It soon became clear that Chopin preferred to concentrate on smaller forms instead of large-scale symphonies, choral works and operas. Fortunately, his composition teacher at the Warsaw Conservatory, Joseph Elsner, had the foresight to let his pupil follow his own path.

Leaving Warsaw for good at twenty-one, Chopin settled in Paris and found himself in the vortex of a thriving intellectual and artistic scene dominated by Balzac, Hugo, Delacroix, Rossini, Berlioz, Auber, the young Liszt and other luminaries. Piano construction had evolved into something close to our modern concert grand paradigm, and virtuoso pianist–composers like Henri Herz and Friedrich Kalkbrenner ruled the roost, pleasing the public with glittery operatic paraphrases, potpourris, battle pieces and other easy-to-digest salon fare.

While Chopin churned out a few opera paraphrases and variation sets of his own, they were informed by an entirely new level of pianistic ingenuity, where new sonorities, figurations and modulatory patterns intermingled to unprecedented, often startling effect. Even in Chopin’s earliest works with opus numbers, the essence of his keyboard style was fully formed. Take, for instance, the astonishing bravura of the seldom-played First Piano Sonata finale’s cruelly demanding double notes, or the Variations on Mozart’s “Là ci darem la mano” from Don Giovanni for piano and orchestra (the work that inspired Robert Schumann’s famous “Hats off, a genius” review). Get past its rather foursquare construction, and the piano writing’s tactile fluidity and judicious deployment are immediately clear, along with subtle harmonic twists and turns not easy to absorb in one hearing.

“More likely than not, Chopin would be baffled by the myriad schools of Chopin-playing that evolved in his wake, all laying equal claim to ‘authenticity.’”

Yet for all of these innovations, a strong classical streak steadfastly prevails throughout Chopin’s oeuvre. That much is clear from the way the composer stuck with absolute forms for his titles (Waltz, Ballade, Etude, Nocturne, Mazurka, Polonaise, Scherzo, Sonata, Impromptu and the like) instead of descriptive or programmatic fodder, as his colleagues Schumann, Berlioz, Liszt and Mendelssohn were apt to use. Beethoven’s thunder appealed to Chopin far less than Mozart’s elegance and proportion and Bach’s organizational powers and contrapuntal acumen. Indeed, Bach’s influence has more than a little bearing upon the 24 Préludes Op. 28. Chopin also adored Bellini’s operas, and it shows: Slow down the Impromptus or the faster Waltzes, sing the glittery passagework out loud, and you’ll discover bel canto cavatinas. Slow down the Fourth Ballade’s thunderous coda, bring down the volume, and concentrate on the top melodic line: an instant aria!

A good guided tour through Chopin’s sound world might commence with the Nocturnes. The form owes much to the development and standardization of the sustaining pedal, which meant that sustained figurations could exceed the normal left-hand span. The Irish composer John Field first applied the word “Nocturne” to lyrical pieces with long, dreamy melodies supported by lilting, broadly spanned accompaniments. In his B major Nocturne, Chopin picks up where Field left off. Seeming simplicity characterizes its opening theme, which comes to a sudden halt at its first climax only to resume in tempo with another idea. Remnants of the original theme reappear like signposts while embellishments and decorations intensify the melodic discourse. Without warning, Chopin shatters his wistful mood with an abrupt, almost violent recitative in B minor, an ending that “defies analysis, but compels acceptance,” according to composer Lennox Berkeley.

It’s a short step from Chopin the poet to Chopin the poet–virtuoso and his Etudes Op. 10 and 25, which many rightly consider the cornerstones of Romantic piano technique. Each of these gems addresses a specific technical challenge, without giving the pianist much respite. At first hearing, the A-flat Op. 10, No. 10 and E minor Op. 25, No. 5 offer catchy, operatically inspired themes within a basic A–B–A song form structure. But notice the slight shifts in texture and phrasing when the tunes repeat, not unlike viewing an object from different perspectives and at different times of the day. Reduce the opening C major Op. 10, No. 1 and closing Op. 25, No. 2 etudes’ taxing arpeggios to their harmonic essence, and you get the bedrock security of a Bach cantus firmus. One wonders if Bach’s organ chorale preludes had any bearing on the E-flat minor Op. 10, No. 6, where a plaintive right-hand cantabile is supported by a chromatically undulating tenor commentary and long, sustained bass lines. The refinement of Chopin’s amazing harmonic imagination here is something to behold, and if you want more where that came from, take a detour towards the coda of the Barcarolle, Op. 60.

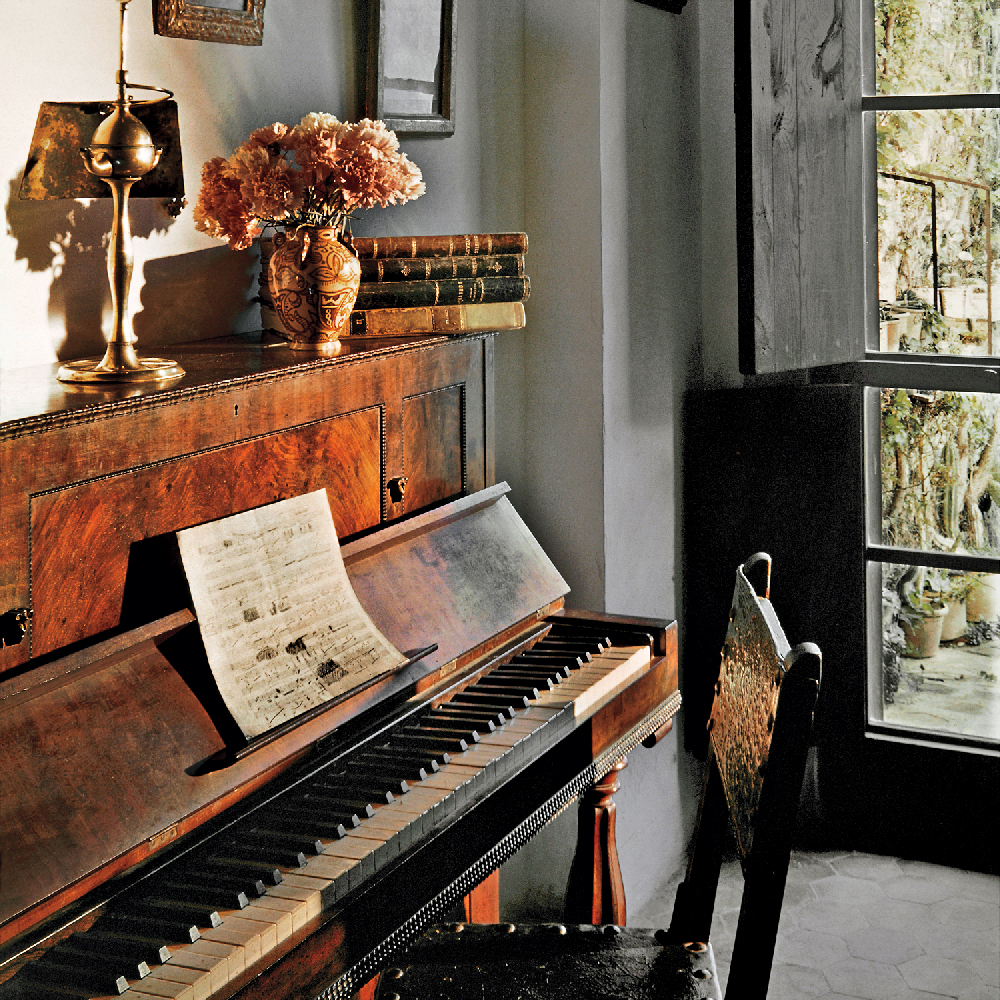

Pianos not included. Chopin ordered this Pleyel piano at the beginning of his stay in the monastery of the abbey of Valdemosa.

Before we add fire and brimstone to the mix, let’s remember that Chopin the performer geared his pianistic gifts to the dimensions of salons and small venues. His playing was about nuance, subtle effects, refinement of touch and perpetual singing, and he left flamboyance, power and audacity to his friend Liszt. What we’d give to hear Liszt wrap his paws around Chopin’s C-sharp minor Scherzo, where musical substance and high-octane virtuosity staggeringly mesh! The angular, declamatory introduction — a kind of compressed opera recitative — dives into a demonic main theme spelled out in stamina-testing octaves. The central, major-key trio features a chorale-like motive answered by delicate descending filigree. When the coda arrives, Chopin works all of the piano’s registers in seeming simultaneity. Chopin’s other principal larger-scaled compositions include the three remaining Scherzi, the four Ballades, the F minor Fantasy, the Second and Third Sonatas, the Cello Sonata (his only mature chamber work) and, of course, the aforementioned Préludes.

One cannot talk about Chopin’s style without acknowledging its deep-rooted nationalism, as borne out in the Polonaises and Mazurkas. Polonaises mostly were lightweight entertainment before Chopin pushed the form into emotionally charged, dynamically volatile keyboard epics (in scope more than size). The swaggering immediacy of the famous A major Op. 40, No. 1 and “Heroic” A-flat Op. 53 stirs up Polish pride in the same way that Americans respond to Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever. However, the F-sharp minor Op. 44 Polonaise digs deeper and, in the right hands, sends shock waves when the sudden, fortissimo upward scales kick in, right after a central episode in the form of a Mazurka. The fifty-seven Mazurkas proper date from Chopin at age ten through his final illness. Their basic rhythms and phrase scansions embrace traditional Polish dance forms such as the Mazur, the Oberek and the Kujawiak while giving free rein to some of Chopin’s quirkiest notions. They constantly veer between simple, complex, charming and audacious, usually within the same opus number.

Take the four Op. 41 Mazurkas, for example. A dark sensibility colors the C-sharp minor’s main theme, only to quickly give way to raucous abandon, huge sonorities and a sudden dying away. The E minor Mazurka consists of a plaintive melody intoned over a restrained, chorale-like accompaniment. Nothing seems to happen in the central episode, but it gradually builds up to a startling key change twelve bars before the end. The A-flat Mazurka is wistful, lyrical and uncomplicated — more like a Waltz. By contrast, the B major’s veiled, opening figure hardly hints at the rising melodic unisons and whirling, giddy passagework lurking around the corner; this is one of Chopin’s briefest, wildest and least known Mazurkas.

For whatever reason, few commentators discuss one particular Chopin fingerprint, and that is his frequent use of repeated notes, either for rhythmic emphasis or to generate melodic intensity. Think of the quick, kicking repeated notes in the Second Sonata Scherzo, the Tarantella Op. 43, the E-flat Op. 18 Waltz’s second theme, the A-flat Op. 34, No. 1 Waltz’s introduction, the E minor Waltz’s main theme or the C-sharp minor Op. 64, No. 2 Waltz’s plaintive chromatic ascending scales. There’s the Op. 9, No. 1 Nocturne’s first theme, the more famous Op. 9, No. 2’s second theme, the Fourth Ballade’s first theme and the folk song quoted in the B minor Scherzo’s trio. What about when Chopin repeats the same note with shifting textures or harmonic movement underneath, such as in the Op. 25 Etudes Nos. 1, 4 and 11? This is not to say that Chopin’s repeated notes are important, but merely to acknowledge their existence.

Few composers for the piano rival Chopin’s staying power and unswerving popularity. Indeed, not one hour goes by without Chopin being programmed, listened to, edited for CD release or practiced on a piano. That was as true a hundred years ago as it is in his two-hundredth birthday year. Chopin would be flattered by the attention, no doubt. But what would he say about his longstanding status as a pop icon? After all, Bugs Bunny has played him, Muzak musicians arrange him, and Liberace unwittingly maimed him. Would he have sued Tin Pan Alley over “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows” (the Fantasie-Impromptu), “Till the End of Time” (the A-flat Polonaise Op. 53) or Barry Manilow’s “Could It Be Magic” (the C minor Prelude)? Not to mention the classic playground ditty “Pray for the dead, and the dead will pray for you” (“Funeral March” from the Second Piano Sonata) and Barbra Streisand’s riotous patter song set to the “Minute Waltz.”

More likely than not, Chopin would be baffled by the myriad schools of Chopin-playing (i.e., French, German, Slavic, etc.) that evolved in his wake, all laying equal claim to “authenticity.” What might Chopin say about the extraordinary, unprecedented proliferation of Asian pianists on today’s scene, all who consider Chopin their own? For his F minor Concerto, would Chopin prefer Lang Lang (born 1982) or Martha Argerich (born 1941) to Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982) or Alfred Cortot (1877–1962)? Would Chopin cringe at or be fascinated by Rachmaninoff’s dynamic alterations in his recording of the Second Sonata?

Stravinsky famously reviewed three recordings of The Rite of Spring back to back; what about Chopin critiquing four wildly divergent interpretations of the Préludes from Maurizio Pollini, Claudio Arrau, Friedrich Gulda and Ivan Moravec? And on the touchy subject of tempo rubato, who would Chopin deem closest to the mark in his Mazurkas: Ignace Jan Paderewski, Ignaz Friedman, Moriz Rosenthal or Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli? Which of Rubinstein’s three remarkably different Mazurka cycles would Chopin download to his iPod? And then there’s the question of instrument: an 1849 Pleyel feels and sounds utterly different from a pre-war American Steinway or a brand-new, hand-built Kawai.

Still, the music itself was built to last, and what Rubinstein said many years ago is likely to remain true for generations to come: “When the first notes of Chopin sound through the concert hall, there is a happy sigh of recognition.”

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.