a journey home

During the pandemic, Steinway Artist Konstantin Scherbakov completed his recording of Beethoven’s complete piano sonatas and has released them — digitally and now as a box set — on the Steinway & Sons label.

By Ben Finane

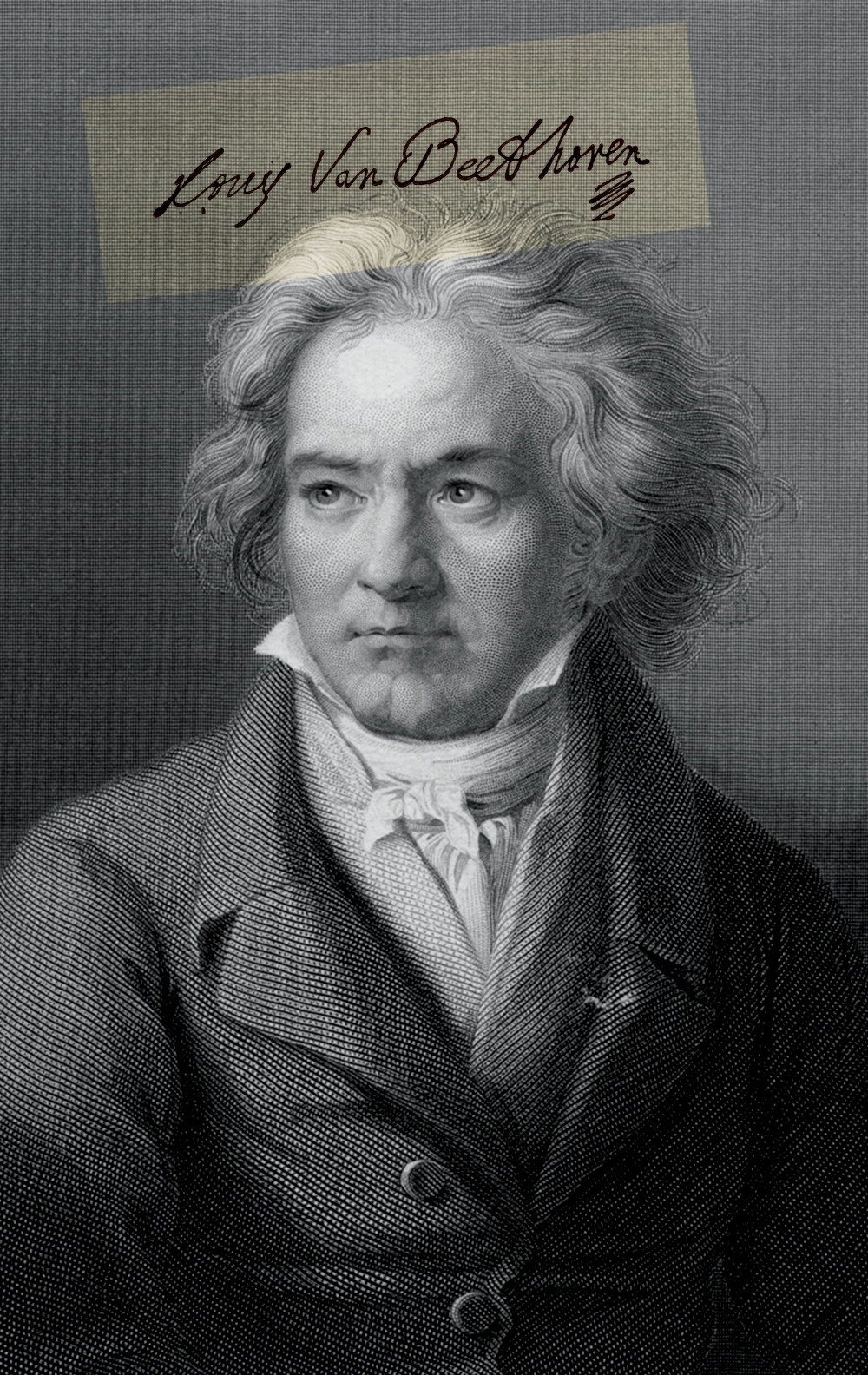

Ludwig van Beethoven (~1770–1827): composer of foundational bedrock of the canon as well as all-time game-changer — an iconoclast who has become an icon. He has been studied, documented, put on the silver screen, fictionalized, turned into a trope and a meme. His 250th birthday this year unleashed a torrent of Beethoven mania across the world — much of which evaporated in the wake of a global pandemic. Yet the recording studio remains — even in times of normalcy — a space of timeless, socially distanced contemplation and craftsmanship, and herewith are the results for Steinway Artist Konstantin Scherbakov — who has steadfastly and chronologically released the Beethoven Piano Sonatas over the course of the year as streaming titles, and now all together, in solid form, as a box set.

The epic myth of the scowling, hot-tempered Ludwig van Beethoven continues to loom over the classical arena and its programs. His epic was heretofore recited to patrons nightly in the concert hall — namely through his symphonies, piano sonatas, and string quartets — and continues to be codified on record. Beethoven’s early achievements found him transforming and transcending 18th-century models, which is to say extending the Viennese Classical tradition inherited from Haydn and Mozart. As Beethoven’s style grew more and more personal, his work grew increasingly profound; he composed many of his masterworks at the end of his life.

The epic myth of the scowling, hot-tempered Ludwig van Beethoven continues to loom over the classical arena and its programs. His epic was heretofore recited to patrons nightly in the concert hall — namely through his symphonies, piano sonatas, and string quartets — and continues to be codified on record. Beethoven’s early achievements found him transforming and transcending 18th-century models, which is to say extending the Viennese Classical tradition inherited from Haydn and Mozart. As Beethoven’s style grew more and more personal, his work grew increasingly profound; he composed many of his masterworks at the end of his life.

The rise of Beethoven contributed to and paralleled the rise of the Artist and the rise of Individuality via originality and invention. To wit, Beethoven infected Classical form with Romantic diversion and side trips. His approach contaminated Classical music to the point where we see the genre through Romantic–colored glasses. Beethoven’s radical approach to composition ushered in a new “Symphonic Ideal” that expanded the range of music itself in the form of a goal-directed framework, interrelated movements, and overarching narratives. His Piano Sonatas, often symphonies for the piano themselves and generally unencumbered by programmatic concerns, freed the composer from any direction other than where his own vision took him. And while Beethoven eventually rejected Napoleonic imperialism, he subscribed to that conqueror’s notion of self-made greatness. His (successful) journey of exploration and personal expression led to his stature as the dominant classical composer of the 19th — and perhaps the 20th? and the 21st? — century.

While the luster of popular music fades with subsequent hearings, a masterwork only gains in brilliance. Yet a masterwork achieves its greatness not through rote repetition but because of a richness of craft and substance that permits it to be viewed from so many angles that a fresh interpretation is always within the realm of possibility. Following Beethoven’s death, the J.S. Bach masterwork The Well-Tempered Clavier gained the moniker of the Old Testament of piano music, with Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas earning that of the New Testament. If Bach’s Old Testament is marked by balance, logic, and discipline, Beethoven’s New sees an engaging personal journey from pastiche to exploration to nothing less than capturing the Universal.

Following the completion of his Beethoven cycle, Scherbakov reflected on his journey:

Konstantin, tell me about the first time you encountered or became aware of the Beethoven Piano Sonatas.

Well, I don’t think there was a first time. Beethoven was simply always there — at home and in the concert hall, at school and in the library where I used to listen to recordings. My father played in the symphony orchestra and every Saturday and Sunday there were two concerts: one by the orchestra and one by the touring soloist. For as long as I can remember, there was always music, and among this music there was always Beethoven: first, the symphonies. I became aware of the sonatas later. But in my first public recital, I played two sonatas: Op. 2/3 and Op. 10/3. I was thirteen years old.

What made you, after that debut, decide one day to say “Okay, I would like to now record all the Beethoven Sonatas?”

After that debut there was a life-long journey in music where for more than forty years Beethoven was my companion. By now I can say that I, with a few exceptions, played almost everything Beethoven wrote for the piano — concertos, sonatas, bagatelles, variations and beyond — all the symphonies in transcription for the piano by Franz Liszt.

However, in the meantime, I have also made a huge circle around the other piano repertoire, with most stops at the suggestion of my labels — the music that is not played often: complete piano works by Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Respighi, complete Concertos by Medtner, Scriabin, Respighi, Tchaikovsky, Arensky, plenty of transcriptions and other repertoire. During the past twenty years I also dedicated much time to Godowsky’s legacy; the recording project of his complete works is now nearing its end. All in all these were extremely intense times when I was constantly studying, playing in concerts and recording new and new pieces. Not all of them were worth attention and effort, between others there were a few works that I did not want to play. So I had a hard time while preparing the first 25 etudes on Chopin’s Studies by Godowsky for recording when I thought, “Oh my gosh, I am really ready now and want to switch the repertoire. I want to play the best music ever written: the Beethoven Sonatas.” This happened one year before the Beethoven’s 2020 Anniversary.

But the anniversary didn’t take place the way we thought it would.

Totally ruined. But back then there was no sign of the pandemic. I was just going to celebrate the anniversary this way like many other musicians. It would be my tribute to Beethoven, a great thing to do and a wonderful present for myself. Besides, after decades of doing many things for my labels, the project Beethoven’s Complete Sonatas would become something that I would do entirely for myself. I was ready for such an endeavor. Now I actually think it is a must for every pianist, once in a lifetime.

Why is this a must-make journey?

After tons of notes that you learned, hundreds of titles played and recorded, it’s like a soul-cleansing experience or, better, it’s like finding your Promised Land after having travelled for decades, your native territory. This music is eternal — since you couldn’t ever fully comprehend the eternity you are at least happy to be able to touch it.

What took you by surprise on this journey as you made it? What advantages do you think were gained by waiting and “saving” Beethoven?

Working on the Sonatas I found out that this music like no other cannot be “interpreted” in the way we commonly use this word for. It does not tolerate any kind of “interpretation” because it is so plain, so clearly expressed, so precisely put down that there is no other way to playing it.

Are you saying the music dictates the interpretation?

That’s very well put: yes; correct. Let’s say you play Chopin — from your imagination, your heart, from your own poetical vision of the world. Your personal expression enriches Chopin’s music and makes your playing very individual, specific as if you wanted to say “Listen: I will open to you my heart, and I will tell you everything about my soul.” And that’s what is needed there.

By comparison, Beethoven is not individualist but a spiritual leader; a poet but a philosopher, an artist but a thinker, a human but a genius. But above all he in his vision of the world is a Humanist who speaks to humanity in the name of humanity. He sums up the experience of humans and puts it down, saying “…Millionen! Here am I to tell you the truth and to lead you to the better world.” Accordingly, the last thing which you are searching for in his music is the “private” note. While playing Beethoven, your task is exactly the opposite: you need to submit to the Idea, to go to the roots of its content, to explore it, to elaborate it in your consciousness, to enrich it by your (very personal!) emotional and artistic experience and, finally, to reveal it to your audience.

This music is eternal — since you couldn’t ever fully comprehend the eternity you are at least happy to be able to touch it.

Not only is Beethoven’s will is so powerfully commanding that you have no other way but to follow (it is notated to the nth degree of precision), but his view imperatively dominates to such an extent that it simply does not permit any personal comment on the part of a performer without the risk of distortion. His music is deeply metaphysical. It is not about sensations, emotions, feelings, thoughts of a single human, but rather a collective, aggregate description of them (isn’t it why it appeals to everyone in the same way and why everyone finds Beethoven attractive and recognizes his own emotional experience while listening to Beethoven’s music?).

To reach such an effect Beethoven invented a wonderfully powerful technique: once a topic is chosen, he puts an idea in a very brief, symbol-like short message and sends it into the world. Most Sonatas begin like this. How can you be “personal” or how can you “interpret” them? The answer is only this: to find the particular in general and in general — the particular, to look for merging of the personal with the collective, the individual with the general. The way which a performer is to make has three stops: to read the message in its encrypted form, decipher it, and enrich the understanding by means of his own artistic vision. The depth of comprehension, the ability to decode information and to bring it over to the listener: these are the major factors that generate the proper emotional reaction in listener’s perception. This is my understanding of the mechanism how Beethoven’s music works.

This is also the answer to your other question. From my sailing throughout the ocean of piano literature I brought here into this project the understanding of importance of proper formulation of ideas, which technically seen is the most powerful source of expression, of its intensity, and the clearness of message. Since the right formulation (or pronunciation) is perhaps the only tool which can bring Beethoven’s idea to full value, the search for it becomes the ultimate goal of the performer. I’m happy that I recorded the Sonatas only now when I’m old enough to have understood this.

Unpack this notion of “the right formulation.”

Let’s take the Fate Motive from the Fifth Symphony, the most obvious and clear example. The composer’s goal is to create a striking impact. To reach the effect he uses his trademark: a shortest possible motive on the base of maximal level of generalization (and recognizability) which is subconsciously, instantly and fully understood and accepted by everyone in

the same way. Performers play it in a hundred ways, which hundreds of recordings show. Comparing versions, you soon notice that not all of them win your heart but rather those which are bringing the idea of the motive to you in the most powerful (read: adequate) way, calling for your emotional response. That’s happening due to the right formulation (you can call it tempo, dynamic, articulation, accentuation or combination of those; together they form Expression).

Here is another example to illustrate the idea of formulation, in connection with generalization: one of my students played a Beethoven Sonata for me, and I asked her what this theme particularly tells her. The answer was, “Well, it’s like, my mother.” I said, “Great, it’s a very suitable idea for that theme, but it shouldn’t be your mother, make sure it is the Mother — everything that you and everyone else associate with the Mother; make it rather a symbol.”

That’s intriguing. I think a lot of people would say Bach is very universal, while Beethoven is very personal. And you’re not saying that at all.

No. Bach is not universal, Bach is the universe itself.

I see.

Bach is all about God, his life and music dedicated to God. In Bach’s universe we get lost instantly. Beethoven’s music is for humans; it all is about humans’ life. It’s like the Bible, if you will, but the music Bible, which speaks of people’s deeds and feelings, about fear and joy, desperation and suffering, hope and belief; it’s about life and death. There is everything you can wish or think of to be found in Beethoven’s music.

I would imagine that your relationship with the Sonatas changes, the way any relationship changes, over time. How has your relationship changed with the Sonatas — both over the course of the project and over the course of your life?

It’s not that the relationship changes, it is that you see and think of far more things every time you come back to this music. Understanding and exploring the content, searching for ever better expression is an endless process. Any recording at any time is only a snapshot, the realization of what you right now trust is the right thing to do. You often get surprised when listening back to recordings made years ago and ask yourself: why did I play it this way? However, that’s inevitable, the world in and around you changes every day, with your mind working accordingly.

The problem arises when it comes to recording Beethoven’s Sonatas. Each of these pieces is something of a monument which should take a certain shape and hold through the times. This becomes perhaps the ultimate and most ambitious task in recording the Sonatas, so that when I look at my recording in twenty years, I can say: “Yes, I still think so.” …And in case this doesn’t happen, I’ll record them again.

“It’s like coming back home into territory that is as natural and native to you as beautiful. It’s an eternal repertory that stands above all.”

— Konstantin Scherbakov

“Scherbakov achieves a high level of control and tonal variety while employing the sustain pedal discreetly. Listen to the way the first sonata Prestissimo’s relentless left-hand triplets take surging wing through finger skill and hand balance alone. Likewise, by not pressing No. 3’s Allegro assai, Scherbakov’s right-hand runs sparkle all the more, with impressive definition and point.”

— ClassicsToday.com

“Scherbakov plays... brightly and with delicacy in spite of his powerful left hand. As expected, his articulation is precise and reflective of the entire tradition of Russian-performed Beethoven.”

— All About Jazz